Ronald A. Wirtz

Director, Regional Outreach

It’s no longer a news story that crop and livestock prices are depressed, given their current multiyear persistence. Feedback from farmers, agricultural lenders, suppliers, and other interests in the ag sector, gathered informally by the Minneapolis Fed over the past year or so in meetings and other venues, has suggested that farm balance sheets are increasingly stressed.

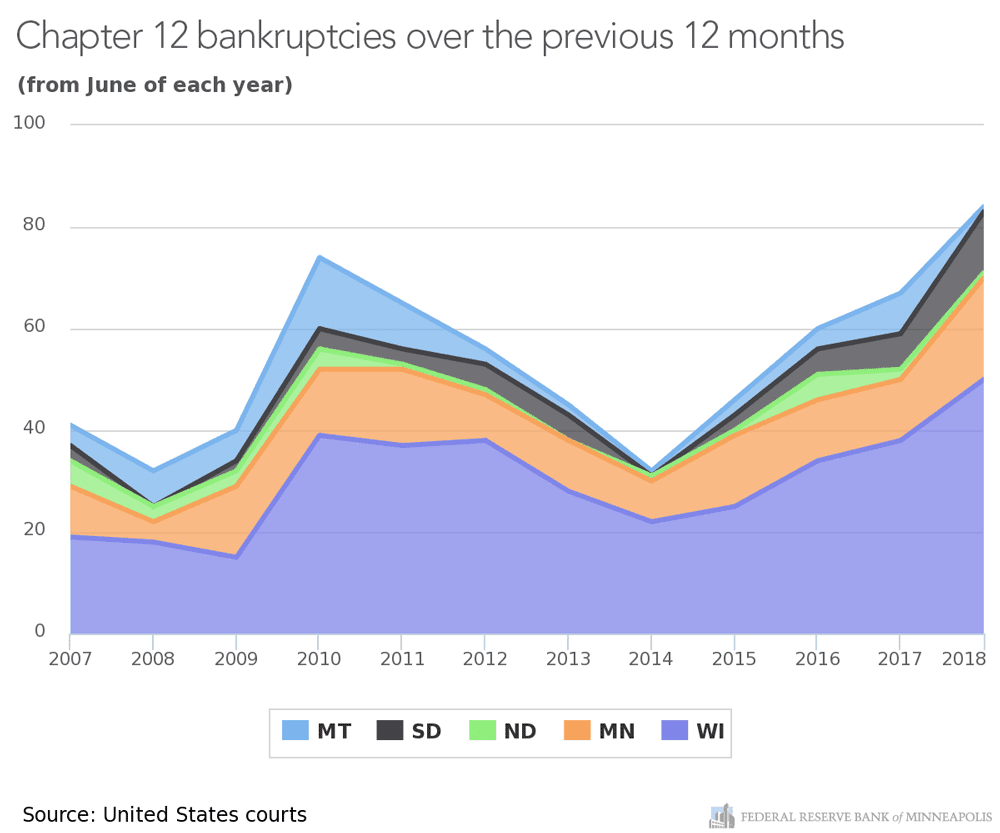

And that nagging economic strain of low commodity prices on farmers and ranchers —compounded for some by recent tariffs — is starting to show up not just in bottom-line profitability, but in simple viability. Over the 12 months ending in June 2018, 84 farm operations in Ninth District states had filed for chapter 12 bankruptcy protection — more than twice the level seen in June 2014.

The trend is both simple and complex. For example, current numbers are not unprecedented, even in the recent past, having reached 70 bankruptcies in 2010. However, current price levels and the trajectory of the current trends suggest that this trend has not yet seen a peak.

Not surprisingly, bankruptcy numbers inversely follow the rise and fall of commodity prices. After a comparatively steep spike in chapter 12 filings during the Great Recession — that 2010 peak — ag prices started rising across the board, and bankruptcies logically pivoted and started to decline. Farm bankruptcies bottomed out in 2014, but again pivoted as high prices reversed and have remained low.

But not all states are feeling the same effects. Wisconsin, for example, is seeing about 60% of all bankruptcies among Ninth District states. It appears that bankruptcy filings have been particularly high among dairy farms there. Though the state is the country’s number two milk producer, it still has many small farms, which tend to be more exposed to large price fluctuations

The average dairy herd in Wisconsin is still just 153 cows; in California, the average herd is 1,300.

Chapter 12 bankruptcy has been around for about three decades, created after the farm crisis of the 1980s, which saw farm debt rise dramatically after crop prices fell and land prices—the leverage used for operating loans on many farms—crashed.

Chapter 12 typically allows for repayment over three years, but as many as five years in some cases. It uses facets of both chapter 11 and chapter 13 bankruptcy—or more accurately, eliminates certain barriers that farmers would face if they sought protection from debtors under either of those chapters of the bankruptcy code.

For example, chapter 11 is typically used by corporations and is more complicated and more expensive to execute. Chapter 13 is typically used by wage earners with much smaller debts. Chapter 12 combines the comparative simplicity of chapter 13 with the higher debt levels allowed in chapter 11. It also provides for payment flexibility, given the seasonal nature of farm output.

Bankruptcies are but one measure of the difficulty in agriculture. Many are leaving the business altogether. The number of licensed dairies in Wisconsin, for example, has fallen by about 1,200 — or 13% — from 2016 through October of this year, according to federal and state data.

Farmers aren’t the only ones hurt by the downturn in ag. The rising trend in chapter 12 bankruptcies aligns closely with a rising level of bad ag loans among the Ninth District’s 531 banks. Bad loans affect a bank’s asset quality, which, in banking jargon, is noncurrent and delinquent loans as a percentage of reserves. So the lower the% percentage, the better the asset quality.

It helps to measure the so-called tail of the distribution — the performance of the bottom 25th percentile of banks. These banks have comparatively poor asset quality to begin with (lower than 75% of all banks) and, as such, the path of their asset quality often acts as a canary in the financial coal mine.

For example, asset quality of ag loans at these banks in the bottom quarter of the performance distribution worsened significantly after the recession. They improved markedly by 2012 and saw a couple of years of very healthy rates (Chart 3). But by 2014, asset quality in this cohort of banks was worsening again. By the second quarter of this year, asset quality would fall below levels seen in the aftermath of the recession — a trend not seen in any other standard loan category, like residential and commercial real estate, or construction and industrial, or even consumer loans.

Maybe surprisingly, asset quality at these lower-performing banks has been declining faster in states — like Montana and the Dakotas — that are not yet seeing dramatically higher chapter 12 bankruptcies. This likely reflects the fact that banks in these states tend to have more ag loans as a share of their total portfolio, and a faltering ag economy is having an outsized effect.

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment